If you hike to the high places in West Virginia’s woods, you may spy a tall structure of wood or steel standing atop the summit. Likely, you have spotted the remnants of a fire lookout tower.

For a time, such towers were the country’s early warning system against wildfires.

The idea for a network of strategically located watchtowers was sparked by a savage wildfire that swept through the drought-stricken western United States. A U.S. Forest Service report on The Great Fire of 1910 said, “Hurricane-force winds, unlike anything seen since, roared across the rolling country of eastern Washington. Then on into Idaho and Montana forests that were so dry they crackled underfoot. In a matter of hours, fires became firestorms, and trees by the millions became exploding candles.” The inferno killed 86 people and incinerated 3 million acres in parts of Idaho, Montana, Washington and southeastern British Columbia.

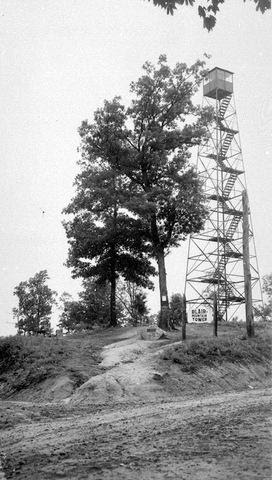

By 1911, the U.S. began to build an extensive system of watch towers to better spot and prevent forest fires. Most of the towers belonged to the state Division of Forestry or the U.S. Forest Service, and a few privately owned by land companies. Depending on the source, the number of fire towers in West Virginia range from 70 to 100.

“A tower observer would spot smoke and take a compass reading,” said Deputy State Forester Anthony Evans, West Virginia Division of Forestry (WV DOF). “The observer would coordinate with other towers in the area to triangulate the exact location of the fire, which was then radioed to the county forest rangers.”

As a youngster, Evans had a close encounter with firefighting that kindled his respect for the elevated watch tower sites.

“The first time I ever fought a forest fire I was maybe 13 years old,” he said. “We made many trips to the fire tower site on Cottle Knob on the mountain behind my house. On one of those trips, we spotted a fire that had escaped from a burn barrel. We helped the landowner put it out before the forest ranger could get there.”

Although hiring practices varied from state to state, the West Virginia Division of Forestry turned to temporary seasonal employees to staff its towers.

“The Division of Forestry did not normally use foresters to staff our towers,” said Deputy State Fire Manager Jeremy Jones, WV DOF. “Each tower would be staffed during our fire seasons or other times of high fire danger. The observers would climb into the towers each morning and stay up there until dark.”

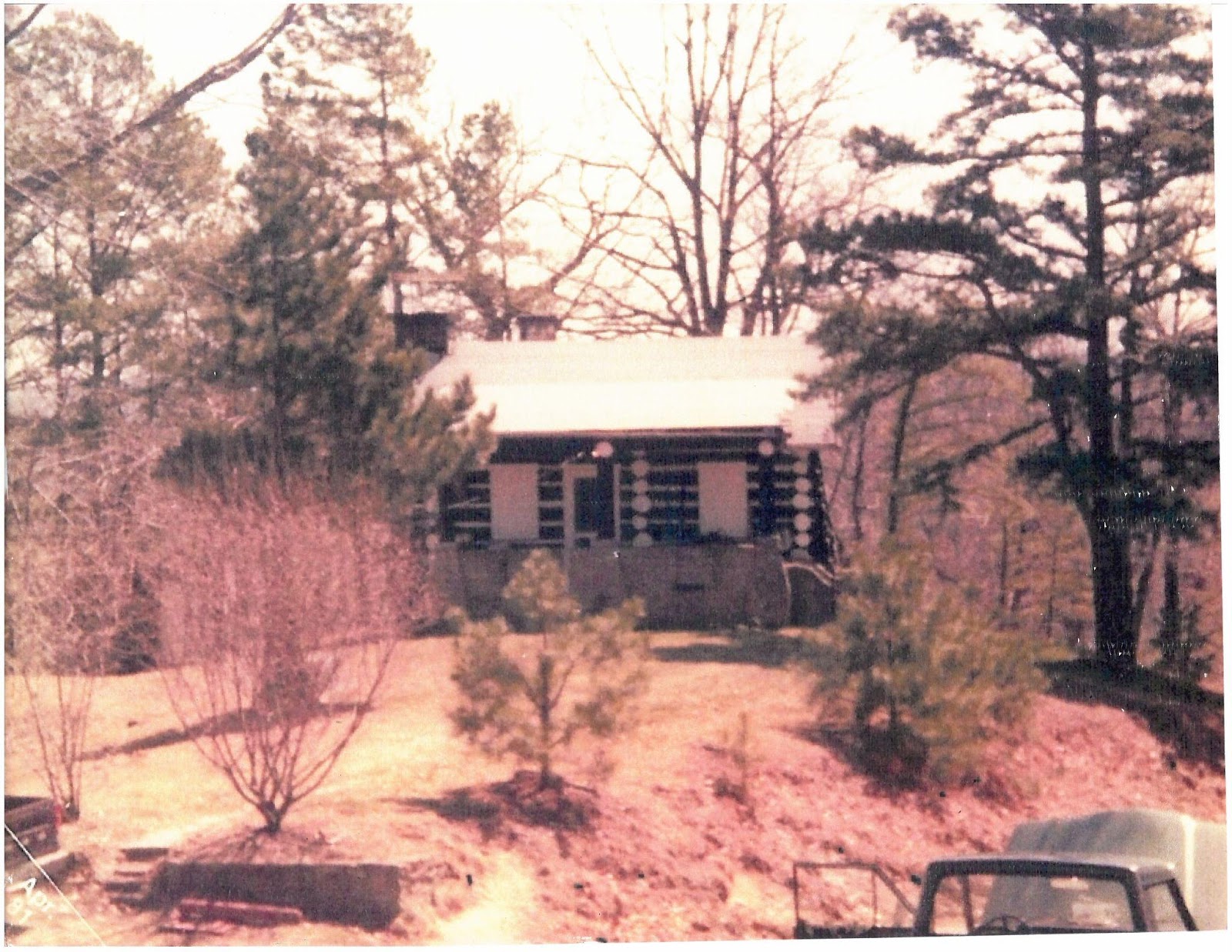

Some observers went home at night. Other tower sites provided cabins where observers could stay. During fire season, observers worked seven days a week. Typically, they had to carry in their own food and water supplies and cook over a wood stove.

As the technology became available, towers were equipped with radio or telephone communications. An observer could spot a plume of smoke and take its bearing with an alidade, a survey instrument mounted on top of a circular topographic map. Observers might also coordinate with two or more other fire towers to triangulate an exact location to report to the district office.

“I have heard some of the older guys tell stories,” said Jones. “Back in those days, the state’s fire occurrence numbers were much higher than they are today. The towers played a significant role in the detection of remote wildfires because we didn’t have the network of roads and such like we do today.”

Fire towers overtaken by technology

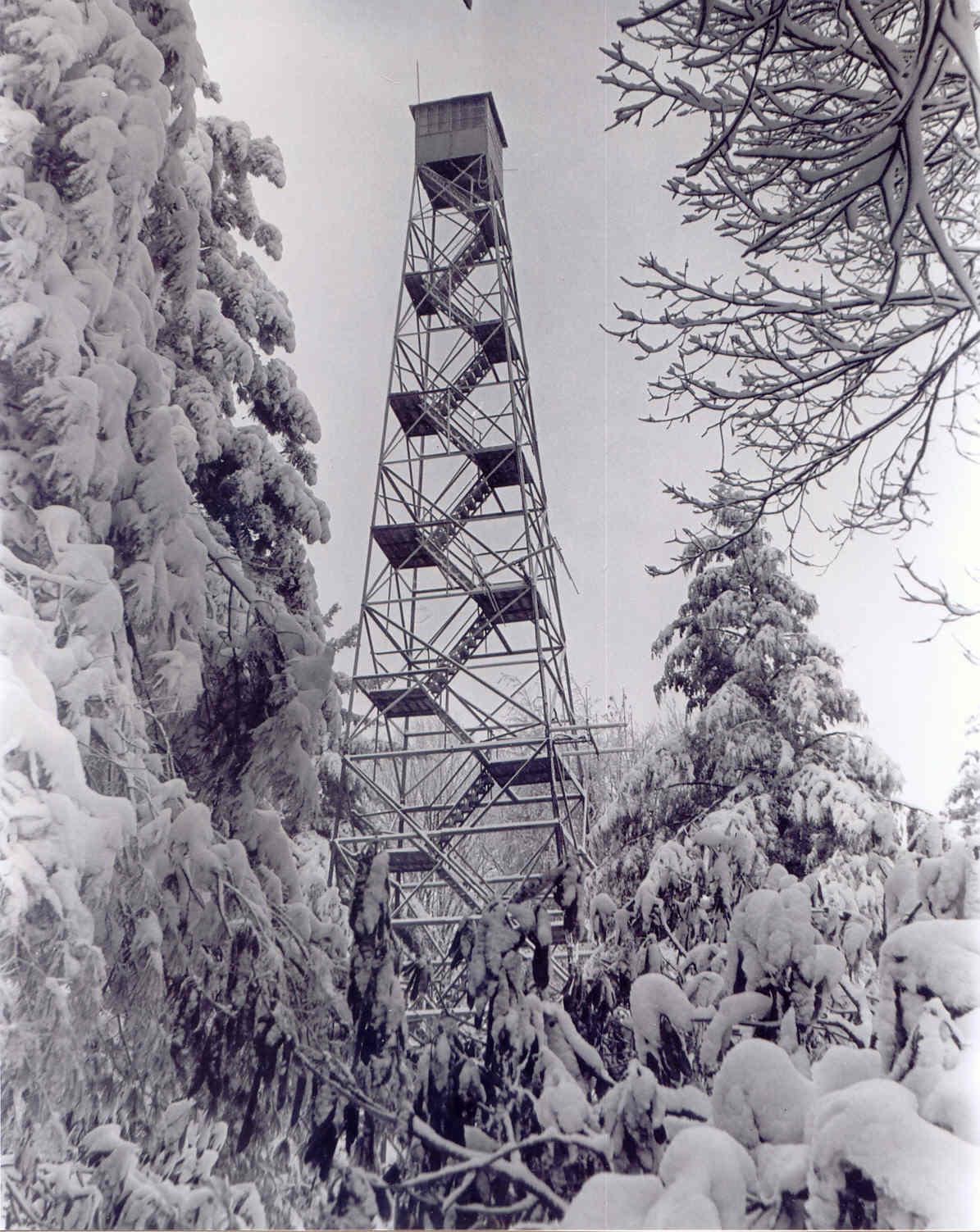

The Monongahela National Forest in the Allegheny Mountains of eastern West Virginia once operated roughly 22 federal fire towers. In the 1960s, it began contracting with pilots and planes to take to the air to scout for fires on the ground. Forest Service spotters accompanied the pilots on flights. By the 1970s staffing for fire towers was being phased out. Most towers were just torn down. A few were taken apart and reassembled elsewhere, serving as public observation decks or other purposes. According to an historical article by the U.S. Forest Service, “of the roughly 22 federal fire towers that protected Monongahela National Forest, only two, Red Oak and Olson towers, remain intact at their original locations.”

Fire towers across West Virginia and the country fell to similar fates.

“We stopped using them because it became more efficient to use aircraft for fire detection,” Jones said. “We still use aircraft.”

County 911 emergency centers, satellites and drones also help fill the role once served by the fire watchtowers.

In West Virginia, a handful of fire towers remain as tourist attractions: Olson Observation atop Backbone Mountain in Tucker County; Bickle Knob Observation Tower; Hanging Rock Raptor Observatory; and Thorny Mountain Fire Tower in Seneca State Forest. The Thorny Mountain Fire Tower is available for overnight rentals.

Both Evans and Jones said they would like to see the surviving fire towers kept up for their historical value and symbols of the state’s history.

“Even when the tower can no longer be climbed,” Jones said, “the locations are still good vantage points for a great view.”